M.A. Bulgakov’s “Future Prospects” and “In the Café”

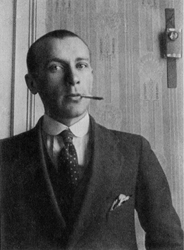

as a student in 1916,

on the eve of the Revolution

and his writing career.

Although the Great War and ensuing revolutions of February and October 1917 produced untold suffering for the peoples of Russia and Eurasia, the destruction and chaos also created opportunities for some members of the next generation. The Soviet Union's most celebrated writer, Mikhail Afanas’evich Bulgakov (1891-1940), author of the famous satirical novel Master and Margarita (Master i Margarita,1928-1940), began his career as a professional writer thanks in no small part to the tumultuous events of 1914-1922. A supporter of the counter-revolutionary White Guards during the Russian Civil War, Bulgakov penned his first publications in response to the collapse of opposition to the Bolsheviks. In doing so, he stepped into the cultural void left by the large number of literary figures who emigrated abroad between 1919 and 1921 to emerge as one of the leading writers of the early twentieth century.

The Great War started while Bulgakov was still finishing medical school in Kiev. He volunteered in hospitals there and at the front until he received his degree and first job in 1916 in the rural town Nikol’skoe, between Moscow and Smolensk. Bulgakov and his wife Tat’iana Lappa received news of the February Revolution while on a short vacation from this post, and soon after were transfered briefly to Vyazma and then in 1918 to his native Kiev. Bulgakov spent some of the darkest days of the war in Kiev, as, within just a few short months, German, nationalist, Bolshevik, and White forces traded control of Ukraine’s capital in bloody battles. When, in 1919, the Bolsheviks gained their final defeat over White forces in that sector, Bulgakov was transferred to Piatigorsk as a White military doctor, where he served in various Caucasian towns including Groznyi and Vladikavkaz.

On November 26, 1919, in the midst of a violent conflict and the terrible gore that he witnessed on the Caucasian battlefields, Bulgakov published his first essay, “Future Prospects,” in the newspaper Grozny (Groznyi). An artistic sketch, “In the Café,” appeared three months later in The Caucasian Newspaper (Kavkazskaia gazeta). Less than a month after publishing “In the Café,” Bulgakov would give up his medical career for good, regretting the years he had wasted in medicine when he could have been writing all along. Soon thereafter, when faced with the Red’s inevitable final victory, Bulgakov and his first wife Tat’ianna Lappa had every intention of emigrating with the Whites. However, during a short trip from Vladikavkaz to Piatigorsk, Bulgakov contracted typhus from an insect bite. He became seriously ill and doctors forbade him to be moved because they feared for his life. While Bulgakov lay prostrate, the Whites suffered their final defeat, and by the time Bulgakov had recovered, the Bolsheviks held Vladikavkaz firmly under control.

Bulgakov’s circumstances during the Great War and Revolution posed incredible personal difficulties: he faced a crisis in his chosen profession after months of witnessing the horrifying effects of war on the minds and bodies of his patients, he suffered from typhus, he did not know what became of his brothers and feared for their lives, at various times he was mobilized by the Reds to serve a cause he staunchly opposed, he witnessed the shameful disgrace of his beloved homeland as cowardice and excuses immobilized the civilian population that would be loyal to a monarchy. By the end of the Spring of 1920, the Whites were driven out of the Caucasus, Bulgakov had recovered from typhus, and he began making his career as a member of the critical intelligentsia in the Soviet Union, heavily engaged in the debate about the role of Russia’s 19th century classics in the culture of the new society.

Formally, both “Prospects for the Future” and “In the Café” reflect tendencies that can be attributed to the peculiarities of wartime prose. During the trials of war, writers often focus more on clear and relevant themes than ornamental layers of language. In both of Bulgakov’s pieces the language is clipped, straight forward, simple; not unlike the kind of prose Ernest Hemingway used to describe WWI in Italy. Setting is minimally sketched, character is portrayed superficially. Thematically, both publications reflect the young Bulgakov’s concerns for the motherland, for the Russia of his youth and heritage. It is overtly anti-Bolshevik, and yet when he speaks of future victory, it is in a distant future, one populated by his generation’s children and grandchildren. By November 1919 it was all too clear that the Whites were in a critical state. Only a few months later, in March 1920, the mass exodus of the Whites and their supporters from Russia would begin. In fact, the theme of a White victory in “Future Prospects” suggests a nod by the author to some form of censorship, an interesting aspect of wartime publications: Bulgakov probably included the inaccurate image of volunteers tearing Russian soil, inch by inch, from the hands of Trotskii to appease White censors.

The primary theme of “Future Prospects” is that of responsibility for the fate of Russia. Russia is being punished, Bulgakov writes, and only future generations will see their great motherland catch up to the west. Blame for this state of affairs rests squarely on the shoulders of the present generation, many of whom who appear willing to wait for others to save their country: Britain, France, other monarchist Russians. Here Bulgakov refers hopefully (and uncharacteristically) to future generations while so many of his subsequent novels noticeably lack children. Bulgakov’s later heroes and heroines may have parents, but they are seldom parents themselves. While the theme of responsibility, parents, and children has long roots in Russian literature, Bulgakov employs a unique image to illustrate the consequences of Russia’s situation: technology. Idle factories depict the stagnation resulting from the Revolution which Bulgakov foresees affecting all areas of a future Russian society. In Bulgakov’s vision, workers fall drastically behind their western European counterparts thanks to the Revolution waged in their name.

The theme of shirking one’s duty as a form of cowardice reappears to animate the fictional scene described in “In the Café.” The gentleman in his patent leather dress shoes represents an able-bodied man who is willing to live in luxury while he waits for his compatriots to free Russia of an invader. He is the worst kind of coward: one who justifies his inaction behind a thin veneer of excuses. The day-dream bravado of Bulgakov’s narrator heightens the hopeless tone of the sketch. The narrator, too, slinks out of the vulgar café, unwilling or unable to even attempt a remedy for the illness he diagnoses.

The effect of the wartime atmosphere are also reflected in the moralistic tone assumed by the narrators of both pieces: ethical concerns outweigh aesthetics. These themes of responsibility and cowardice show up again in Bulgakov’s later prose, but they reflect the ambiguity that the luxury of peace (and, perhaps more urgently, the pressure of a hostile censor) brings to an author’s perspective. In these early publications, the narrator’s voice is clear and decisive. He knows what should be done and does it. The tone takes for granted that the author is himself thoroughly engaged in the conflict against the Bolsheviks. Exactly what type of engagement this may be remains unclear, a conspicuous omission, but perhaps Bulgakov assumed his readers would read the omission as humility rather than hypocrisy. In later works like White Guard (Belaia gvardiia, 1923-24) and Flight (Beg,1926-28; published posthumously,1962), Bulgakov’s heroes are much more three-dimensional. They conduct themselves with honor, though their honor leads them only to defeat, infamy, or base survival.

Both “Future Prospects” and “In the Café,” are interesting in their own right as examples of literary production during the Civil War. They are no less significant for providing insight into the early development of themes and images that would appear in Bulgakov's later works and posthumous adaptations of his works. The themes of cowardice and responsibility developed in “Future Prospects” would play central roles in White Guard, Flight, and Master and Margarita; the vulgar setting of “In the Café” is reincarnated in two telling variants.

Bulgakov recycles the café setting in the third scene of the second act of Black Sea (Chernoe more, 1936), a libretto written for the Bolshoi theater. The White general Agaf’ev enters a café packed with civilians, where a gypsy ensemble performs on a stage. When asked to give a report on the state of affairs, Agaf’ev enthusiastically describes the city’s impenetrable defenses. The artist Bolotov approaches the general to request help on behalf of his ill wife who is being unjustly held in the White counterintelligence headquarters. Before the general can act on this request, he receives news that the Reds have broken through the city’s defenses and he falls over dead. Everyone flees the café, hysterically racing to board the last ships preparing to leave port.

In the film Flight (Beg, 1970), which incorporates various elements from several of Bulgakov’s works about the Civil War, the screenwriters include a café scene similar to the ones in Black Sea and “In the Café.” White counterintelligence officers attempt to delay Korzukhin, a high official in the White government, by entertaining him in a café. Their goal is to delay his passage to the West long enough to extort a considerable sum of money from him to clear his former wife from false accusations of spreading Communist propaganda and participation in underground communist activity. Watch the scene from Mosfilm’s Flight with English subtitles here (1:03:56-1:06:25).

The café scene in each variant is brief and limited, and yet vividly suggests what life in Russia’s southern cities was like as the Bolsheviks advanced further and further south and the demise of Denikin’s army became inevitable. In the face of national calamity, the bourgeois café scene remarks powerfully on the inherent duplicity of wartime life, highlighting the contrast between privation and privilege. In “In the Café” Bulgakov seems to use the café to motivate Whites to recognize the duty of honor, to stop their hypocrisy; in Black Sea the scene underscores the empty security and cowardice of the White High Command. In the Soviet film version, writers (with the approval of Elena Sergeevna Bulgakov, the writer’s third wife) employ the power of the imagery to reinforce negative stereotypes of the bourgeois Whites.

Wars do strange things to the fates of individuals. Bulgakov completed his education during the Great War and practiced medicine through the end of Russia’s engagement in that conflict. He experienced the nightmarish taking and retaking of Kiev, and worked through the Civil War as a doctor. Then, on the eve of the end of the conflict Bulgakov made his first professional marks on the world of Russian literature in these two seemingly inauspicious newspaper publications. While so many of his elder contemporary writers (Bunin, Ivanov, Shestov, Artsybashev, Kuprin, Bal’mont, Merezhkovskii, Hippius, and others) were leaving the country, Bulgakov lay ill with typhus and missed his chance to get out. But those emigré writers, most of whom would never return, left a gaping whole into which Bulgakov was able to step, switching careers from medicine to belles-lettres to become one of the Soviet Union’s greatest fiction writers.

Download Sidney Dement’s complete English translation of "Future Prospects" in parallel text.

Download Sidney Dement’s complete English translation of "In the Café" in parallel text.